Punch, or the London Charivari is a wonderful source for history of science. It is impossible to think of a popular magazine today including jokes that span politics, science, the arts, classical reference and what we might call observational comedy. As with the image posted on the Ptak Science Books blog the other day, the editors of Punch had high expectations of their readers’ ability to recognise not just a handful of scientific celebrities but a while range of figures from the scientific community. Those of us who have commented on John’s post are struggling to be sure of the identities of some of those represented, or to explain just what the mathematician is doing with a fish that has so shocked a zero (have a look – and let me know if you can explain!).

In the comments, I pointed to the existence of the SciPer Index, created at the HPS department in Leeds between 1999 and 2007. This indexed short runs of sixteen 19th-century periodicals, creating a online resource and three important books.[1] While the project suffered from being at the head of the game – being superseded in many ways by mass digitisation projects, which cover much longer runs of periodicals with full images – it remains immensely impressive in terms of the added value created by the project members. This is not just a word-searchable set of texts, but a real index, explication and glossary.

For something as visual and complex as Punch, this is exactly what is required. The image on John Ptak’s site is nothing to a search engine until it is described in words. And the SciPer Index not only describes, but identifies and connects. It is not, of course, infallible: the dedicated scholar-indexers occasionally missed or misidentified references, and had to make complicated choices about just what we, or 19th-century writers, define as ‘science’, but it is the only thing I know that really spells out just how prevalent, and how intricate, such references were at this period.

I often come back to Punch, especially as I was lucky enough to inherit a set of bound 19th-century volumes. Because I have recently been thinking about the historic transits of Venus, I was looking today at the 1874 and 1882 volumes, knowing from Jessica Ratcliffe’s The Transit of Venus Enterprise in Victorian Britain (2008), that there are some great illustrations, revealing popular interest and the imperial and nationalistic agendas bound up with the transit expeditions. More of those another time – one will certainly be making its way into the exhibition at the Royal Observatory this spring. What struck me today, leafing through these volumes, is just how many references to science are there each year. Take a look at the SciPer Index for earlier volumes to see what I mean.

I will share just a couple of 1874 astronomical examples (a year that saw a comet and a transit of Venus), otherwise I could be here all night….

THE ASTRONOMER AT HOME

I hold, whatever PROCTOR writes,

Or LOCKYER, or AIRY,

Out-door observing, these chill nights,

A snare to the unwaryLong though you gaze into the sky

(Not quite, I hope, cigarless),

What chance of seeing meteors fly

Through a heaven that hangs starless?A blazing fire in bright steel bars

Best observe, after dining;

And study – if you must have stars –

Those ‘neath arched eyebrows shining.Transit of Venus snugly watch.

With comforts that enhance it:

There is no place like home to catch

Your Venus in her transit.Let who will, ‘mid Kerguelen’s snows,

Seek freezing-post and thawing-room,

My Venus one short transit knows –

From dining-room to drawing-room.Let me observe her, by lamp-light,

In chaise longue, soft and lazy,

Her witch-face framed in hair-wreaths bright,

Enough to drive one crazy.Sweet star of eve, whose beauties blend

With foam of vaporous laces,

That like a cloudy setting lend

A mystery to thy graces,Heightening the charms they half enwrap –

Sweet star too of the morning,

In muslins fresh, and pretty cap

A prettier head adorning!Yes, “Vive l’Astronomie,” say I –

But what I add between us is –

While our Home-Heavens can still supply

Observers with their Venuses!

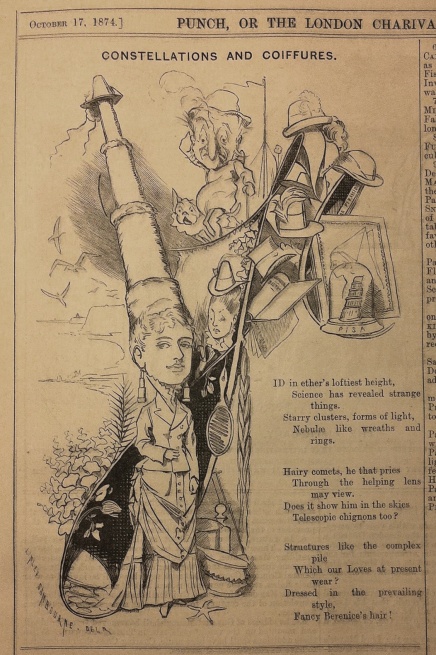

Not the best poetry – though kudos for rhyming “Venuses” with “between us is” – and rather sickly sweet than funny, perhaps. There is little to hint at the strides that women were beginning to make in education and public life at this date. However, this image ‘Constellations and Coiffures’ does something distinctly different:

The joke, of course, is about the fashionable new hairstyle, but it takes its range of astronomical references for granted. A telescopic chignon was, of course, apt for a comet, ‘long-haired’ being the literal meaning, though please note too the telescope earrings. Ether, nebulae and cluster are also thrown into the accompanying poem. At the end, “Berenice’s hair” refers to Coma Berenices, formerly part of Leo and now a constellation in its own right. It was named after Queen Berenice II of Egypt, who swore to sacrifice her long, blond hair to Aphrodite if her husband Ptolemy III Euergetes returned safely from war. He did, and she placed her hair in the temple. It disappeared and, the story goes, the court astronomer, Conon of Samos, appeased the angry king by claiming that the gods were so pleased by the hair that they had taken it and placed it in the heavens.

A source of early feminism Punch is not, but as a source for developing an understanding of the role, meaning and cultural baggage of science among the Victorian middles classes it is, undoubtedly, essential reading.

———-

[1] These were Science in the Nineteenth-Century Periodical: Reading the Magazine of Nature (CUP, 2004), Culture and Science in the Nineteenth-Century Media (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 2004) and Science Serialized: Representations of the Sciences in Nineteenth-Century Periodicals (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 2004).

[…] politics, science, the arts, classical reference and what we might call observational comedy. [Read more] Share this:Like this:LikeBe the first to like this […]

Nice post, Becky! The newsy poems remind me of those which often appeared in eighteenth-century newspapers and periodicals as well. A pretty well-known example is the poem which appeared in the ‘Gentleman’s Magazine’ in 1764 about the ‘race’ to become the next Astronomer Royal:

GREENWICH HOY!

or the ASTRONOMICAL RACERS

Two lunar months are past, and more,

Since of these heroes half a score

Set out to try their strength and skill,

And fairly start for Flamsteed-Hill,

But lo, form doubts, or fears, or surfeit,

Six have drawn stakes, or else pair forfeit;

and thus there now remains no more

To run the match, than doughty four

The first who vaunts the race he gets,

Is affluent professor B—ts;

Whose first of April’s lunar map

Has giv’n his judgement such a rap,

As to induce his warmest friend

To wish no longer he’d contend;

Who owns the place his only view;

The business journeymen may do.

The N—b’s brother next advances,

Who, with some mettle, skips and prances:

But take car, Rev. M-sk-l-n,

Thou scientific harlequin,

Nor think, by jockeying, to win:

Why, when the foremost in the course,

Woulds’t thou thy hopeful chance reverse,

Avouching with ungen’rous mind

The two most worthy had declin’d?

Believe me, this fallacious boast

Has run thee the wrong side o’ the post:

For the great donor of the prize

Is just, as Jove who rules the skies.

The next, who promised some sport,

Is the renown’d optician Short;

Who, cautious, acting like a man,

Makes all the interest he can,

And candid hopes, if he should fail,

Experienced Nestor may prevail.

Nestor, aloud, the standers-by,

Looking around with pleasure cry –

And will thou, Bevis, wilt thou venture

Against such hardy weights to enter?

Yes, clear the course, and call the grooms,

For lo! How he attended comes

Tho’ no professorship you hold,

No fellowship endow’d with gold,

No pension on this worldly satge,

To comfort thy advancing age,

Yet has the Prussia hero deign’d

To fix thee ‘midst his learned land.

Courage! then Sir, nor drop thy spirit

Thy royal master’s heard thy merit;

And that the world with outstretcht eyes,

Looks on, and points thee for the prize.

Nay, singly ask the other three,

On whom (himself excepted) he

Thinks that the dubious lot should fall,

Bevis, they’ll answer – one and all,

Keep then this adage old in view

That what all say must sure be true:

And ‘gainst the field, I think we may

Venture some odds – you get the day.

C.P.

Pall Mall,

December 24th 1764

Yes, thanks Alexi – I know this one from Howse’s biography of Maskelyne. It’s full of fascinating allusions! It’s hard, though, with this kind of evidence to decide how much the writer really knew about the situation, how much was gossip and how much just threading together a few bits of detail and knowledge. It’s tricky evidence to handle (although I know you’re an expert!).

With eighteenth-century longitude pieces, it definitely seems like some of the commentators and satirists didn’t really know much about ‘the search’ and certainly about the relevant mathematics, astronomy, navigational techniques and so on and were just scoring an easy point because ‘everyone’ knew how wacky those (longitude) projectors were and how elusive the coordinate was!

I also wonder whether or not the wonderful ‘Constellations and Coiffures’ cartoon was simultaneously commenting on female fashion, which could be ‘representational’ / figural (and was still sometimes derided as extreme or silly) during the 1800s. For example, there was tons of jewellery produced over that century which was meant to represent specific comets, although it was produced for men as well as women. Example: http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O115272/brooch/

Absolutely! It was, above all, satirising large chignons – a new fashion for the 1870s that is targeted elsewhere in this volume. Chignons and bustles take over from jokes about the huge crinolines of the 1860s. The telescope earring must certainly refer to comet broaches and thhe like, as well as other novelty ornamentation (it’s not long, I think, before there was a fashion for electrical jewellery, with large batteries hidden under dresses). I’m sure that on top of this is the joke that women use scientific iconography for fashion, of feign a general interest, without, of course, the real understanding the men of science would have.

[…] (Via teleskopos) Written by admin Posted in Archive, Google Reader Tagged with Favourite, Google Reader, teleskopos […]

[…] has a whole bunch of really excellent post starting with Objects and Storytelling and ending with Mr Punch does Transits. Go read them all its more than worth […]

The mathematical guy is a puzzle. The SciPer Index says that it’s Babbage, which I think must be wrong as he was 73 at the time. Certainly whoever it is must have been very well known, as he has no identifying label. I don’t think it’s Sylvester, who would have been 50 and, I suspect, already looking 70; I’ve never seen a picture of him where he isn’t bald and with a flowing grey beard. H J Stephen Smith presented the sixth part of his long report on the Theory of Numbers, and at 38 he was of the right age; but to me it doesn’t look like him, he wasn’t well-known to the general public, and there seems to be no explanation for the behaviour of the zero.

My money is on William Thomson, who at 41 was the right age and who wore his hair as in the cartoon:

In the photo he seems to have a very short fuzzy beard, which also corresponds with the cartoon. He was already a very well-known public figure, having been intimately involved with the trans-Atlantic cable project and travelled on all the cable-laying expeditions. I think that that explains the reference to a fish, but it may also be a sort of rebus, if the fish is thought of as a perch: got a perch = gutta-percha, the wonder material that was used in the cables as an insulator and adhesive. I’m stumped by the thing hanging down from the fish, though; it could be half of another fish, which seems a bit pointless, or perhaps a section of cable – it seems to have a tube running through it.

There were two papers at the meeting on the subject of the cables: Mr William Fairbairn on Some of the Causes of the Failure of Deep-sea Cables, and Experimental Researches on the Permanency of their Insulators; and Mr C W Siemens on the Outer Covering of Deep-sea Cables. It was clearly a live issue.

The numbers, I suspect, refer to Thomson’s being a Second Wrangler, and to his Absolute Scale of Temperature; the zero is fleeing because it has been banished from the universe as the unattainable lower limit. This is probably pretty far-fetched, but I can’t think of anything better!

Why does Brewster’s stereoscope have two little feet sticking out at the front, and two little hands at the sides?

Thanks John! I had a feeling that my suggestion of JJ Sylvester had to do a discussion you and I had when I first came across that cartoon while doing my PhD – but perhaps not! I was also partially convinced by this alleged and poorly-reproduced portrait: http://artsandsciences.virginia.edu/mathematics/aboutus/history/bios/sylvester.html

I definitely agree that’s it’s not Babbage – Thomson is looking possible… I like the terrible perch pun!

That said, is the thing hanging from the fish not a price ticket? In which case, the joke might be “what has that got to do with the price of fish?” – ie everything at the BAAS is potentially obscure and irrelevant. The zero maybe particularly affected by such irrelevance?!

Not sure we’re quite there yet…!

As for the stereoscope, there’s plenty of other such anthropomorphic tools, instruments and concepts in this image, so I don’t think it’s specific to Brewster and his case. As to what it means more generally, I’m not quite sure. Something to do with the fact that these inamimate or mute things are given so much attention by these men that they’ve been given a life of their own? The intelligent men are being led a merry dance by their tools? Something like that…

Yes, there are plenty of anthropomorphic tools but, to me at least, Brewster’s stereoscope doesn’t look like one of them. The legs and arms are not attached to the instrument, and indeed it couldn’t stand up or move with the legs positioned as they are. Rather, they are sticking out from inside the body of the instrument, as if a little person is trapped in there. So I was wondering whether that referred in any way to the kind of work on which Brewster was engaged!

I think that’s reading too much into it…! (Could be wrong, of course.)

I have no idea about the screaming zero, or the mathematician’s identity, but a bit of digging around in Google Books leads to an explanation of the fish-and-a-half and its price label.

It’s simply a reference to an arithmetical brain-teaser: “If you can buy a herring and a half for three halfpence, how many herrings can you buy for eleven pence?” (or fivepence, or a shilling…) This appears, for instance, in Lydia Child’s _Girl’s Own Book_ of 1833, and apparently did the rounds of children’s miscellanies and instructional texts.

The form of the question was memorable enough to make it a comical stand-in for tricky calculations in general. It was often parodied: _Punch_ for 1844 has “if a red herring costs three halfpence, what will a sack of coals come to?”, and by 1865 _Fun_ was pointing out that “If a herring and a half cost three halfpence you had better have two for breakfast, and hang the expense!”

The fish riddle pops up again in _Punch_ for 11 November 1865, page 190, not long after the BAAS meeting parody, but in an apparently unrelated squib about Benjamin Phillips, Lord Mayor of London (I think). “A problem so abstruse,” runs the text, “might possibly have puzzled the Senior Angler at Cambridge.” Indeed.

That seems to have settled the fish question beyond doubt. And it saves me from having to suggest a possible reference to Poisson’s Law of Large Numbers!

Hey, great post Becky – _Punch_ is indeed a wonderful resource for the nineteenth century, and certainly needs something like SciPer to help one make sense of it!

On the identity of the mathematician, I thought at first that it was William Thomson, because it does look a bit like him, though I couldn’t work out the symbolism of the numbers and the fish. If James’s suggestion about the fish is on target, though, I think it must be someone generally regarded as a mathematician, and there wasn’t anything particular to target them with, beyond general references to arithmetic. This makes me doubt it’s Thomson (was he even at that meeting? – I thought he was off laying cables.) I also wondered if it has to be someone well known enough not to need further identification – Owen, Huxley and Murchison all have little name labels, and they were widely known in 1865. That might be plausible for Sylvester – I don’t really know how famous he was in 1865 – but I wondered if it might be William Spottiswoode. He was President of Section A in 1865, and would have been about 40, though I haven’t found a portrait of him from that period, only later ones, in which he has a long grey beard. Also, if the numbers are supposed to represent the members of Section A, it could refer to Spottiswoode’s opening address, which may, to judge from a couple of newspaper reports, have gone on just a little bit, so could it be that the audience is beginning to get restless? They would obviously leave in numerical order, so the zero goes first – does that sound plausible? In terms of fame, if I remember right, Spottiswoode had made a good marriage and gave parties at the height of the Season which the cream of science and government attended, so was as famous for his social life as for his science by this time. Any good?

Many thanks James and Leucha! I’m very glad we’ve sorted out that fish and a half! As far as the zero goes, I am tending toward the view that it is simply running way from the tediousness of the lecture, its shape best representing an open mouth (hat tip to @ianppreston on twitter).

Judging by this image http://t.co/h93U67je, among others, I am very much tending to toward the consensus that it is Thomson. It would appear that the artist was a little behind the times – lacking reference to the telegraph cable or Thomson’s burgeoning beard. This site suggests that at the time Thomson already had a fairly lengthy beard: http://atlantic-cable.com/Books/1865%20ATHistory/index.htm He probably wasn’t at the meeting either: after losing the cable, the Great Eastern landed in Ireland on 17 August – a bit of a rush for the September meeting in Birmingham, particularly when he was expecting to be away.

So – an image full of relevant detail, yet not quite with its finger on the pulse (as it were).

I’m not convinced that the reason the zero is running away is the tediousness of the lecture. This would surely be far too discourteous, and anyway not something that would have occurred to the cartoonist, since it appears that Thomson didn’t present a paper. Maybe the zero is just horrified by the arithmetical difficulty of the fish problem!

Yes, agreed – tediousness wasn’t really the word I was after.

Hi, I wonder whether anyone knows what was the ‘fallacious boast’ made by Nevil Maskelyne referred to in the third verse of GREENWICH HOY on p.595 of the December 1764 issue of The Gentleman’s Magazine (quoted by Alexi above), that supposedly put him on ‘the wrong side of the post:’ ?

Given that the poem was published in December 1764, before the lunar distance results during the trial had been discussed by the Board of Longitude (and before relations with William Harrison had deteriorated – what was claimed, for example about their relations in Barbados, was written some time after events) I don’t think it refers to the 1764 trial. It’s possible that the “fallacious boast” refers to the excellent results Maskelyne claimed for lunar distances after his St Helena voyage and in his British Mariner’s Guide (1763). However, I think that the poem is actually simply focusing on the “race” for the “prize” of being made Astronomer Royal. His “fallacious boast” is that the other candidates have withdrawn, and this “jockeying” in itself will disqualify him.

I agree that the language in the poem is purposely over-exaggerated in order to cast the competition for Astronomer Royal as a thrilling horse race as well as to depict Joseph Betts and Nevil Maskelyne – ‘the Nabob’s brother (in law)’! – as less worthy candidates than the author’s choice John Bevis. (Bevis and Short were also friends of the Harrisons, who viewed Maskelyne with his lunar distance advocacy as a potential competitor for a longitude reward – but who knows whether that also contributed to the author’s negative feelings towards M.) Unless worded poorly, it does seem to accuse Maskelyne of having claimed that some of his competitors had withdrawn themselves from consideration – which is not something I’ve yet seen mentioned anywhere else, so I wouldn’t pay it much mind unless someone discovers corroborating testimony/evidence.

I do think, however, that the author and other interested parties are likely to have had some idea of what Maskelyne had been doing during the voyage to Barbados in 1763-4 and that he was reporting favourable results even before the relevant Board meeting. There was clearly information – some accurate and some not – coming back to the UK over the course of the voyage through a combination of letters (from actual participants and from outside maritime and colonial observers whose paths they crossed etc.) and publications (drawing upon letters, rumours, and covert ‘puffing’ – mainly Christopher Irwin & co playing up his marine chair and sometimes from Harrison & co). The periodicals kept an eye on the proceedings from summer 1763 onward, most often because of the public interest and/or successful puffing of both Harrison and Irwin but sometimes inclusive of Maskelyne and the astronomical efforts.

The author of the poem would surely have also been aware that Maskelyne had indeed been actively ‘jockeying’ for the Astronomer Royal position in recent months, by contacting and soliciting testimonials from his learned and powerful friends which he then submitted to the government. This was not at all unusual – it was as common for early modern jobseekers to solicit and provide written testimonials about their character and skill, as it is for people to provide references today. But perhaps the author, being for Bevis, did not take kindly to the younger astronomer’s determined efforts!