I had a bit of fun this week tweeting links to portraits of some 19th-century men of science, suggesting that they were ’19thC scientific hotties’. Such a phrase is not, I should add, my usual vocabulary, and nor is a focus on people’s looks. And thus explanation is in order. My tweets brought a response from Vanessa Heggie – “trying to tell myself this ‘historical hotties’ thing is OK, as is clearly subversion of patriarchal power” – and linking to Bangable Dudes in History. Was I making a feminist point? Or was I objectifying these men in a way that I would naturally find uncomfortable if it were living women? Was I, perhaps, attempting to claim that men of science can be attractive, in some sort of historical, masculine version of the (for me) dubious Cheerleaders for Science.

I was, in fact, playing with a few ideas that I didn’t want to develop in 140-character chunks on Twitter. One was exploring this as a hook for introducing less-well-known scientific figures to an unsuspecting public, another was thinking about how such men chose to be portrayed in their lifetimes, and the third was my own response to these portraits, and how they may have coloured views of these historical characters.

The whole thing started in response to this post by Beth Dunn on Thomas Say and the utopian project that had Robert Owen sending a ‘Boatload of Knowledge‘ – in the form of men of science, writers and artists – to New Harmony in the mid-West. It was not Beth’s contention, but someone had suggested that Say was a “19th century hottie”. I retweeted the post, but also suggested that I had another favourite portrait of a man of science and adventurer, the NMM’s portrait of James Clark Ross by John R. Wildman.

Ross, who travelled to both the Arctic and Antarctic, located the north magnetic pole and carried out a huge range of scientific observations, was reckoned by Jane Franklin “the handsomest man in the navy”. He was the “scientific serviceman” par excellance: a heroic naval figure who could cut a dash and demonstrate his manly devotion to nation in time of peace. He’s fascinating, but I don’t fancy him (he’s dead, for a start), I just love the portrait: a Romantic shock of dark hair, passionate glance, icebergs, polar bearskin, Pole Star and, beautifully delineated in the foreground, an instrument known as a dip circle, used to measure variation in magnetic inclination.

As my tweet got a reasonable response, I followed it up over the next couple of days with links to Thomas Phillips’ portrait of Michael Faraday and Thomas Lawrence’s portrait of Henry Brougham. Again, these are Romanticised images of men who, in very different ways, took on public roles that were undoubtedly enhanced by their intelligence and charismatic personalities. Faraday was, of course, a star public lecturer (the Brian Cox of his day, dare I say?) as well as a hugely important figure in the history of chemistry and physics. Although modest and discrete, he certainly knew – or learned – how to capture his audiences through look, voice and gesture as well as knowledge and dexterity. Brougham, in reality, was probably no looker but I was captured by his portrait when it was displayed in a NPG exhibition, The British Portrait 1660-1960, way back in 1991 (when I just about knew of the Great Reform Act, but had never heard of history of science). It is Lawrence at his best: capturing a light of fierce intelligence in the eye of this young, ambitious, passionate lawyer.

I think I would have to admit, if challenged, that my knowledge of these portraits probably pre-disposed me to some level of sympathy for the sitters. Quite probably it was more than I might have felt had I first seen their much later photographic portraits. It’s never nice to admit, but looks and first impressions inevitably colour our impressions of people and, I think, the same can be true of those we meet through paintings and archives, although better acquaintance can often override early opinions. Other times, an interest, familiarity or admiration can build up from knowledge of the archive, only to be challenged when finally seeing a portrait that misses by a country mile the mental image built up.

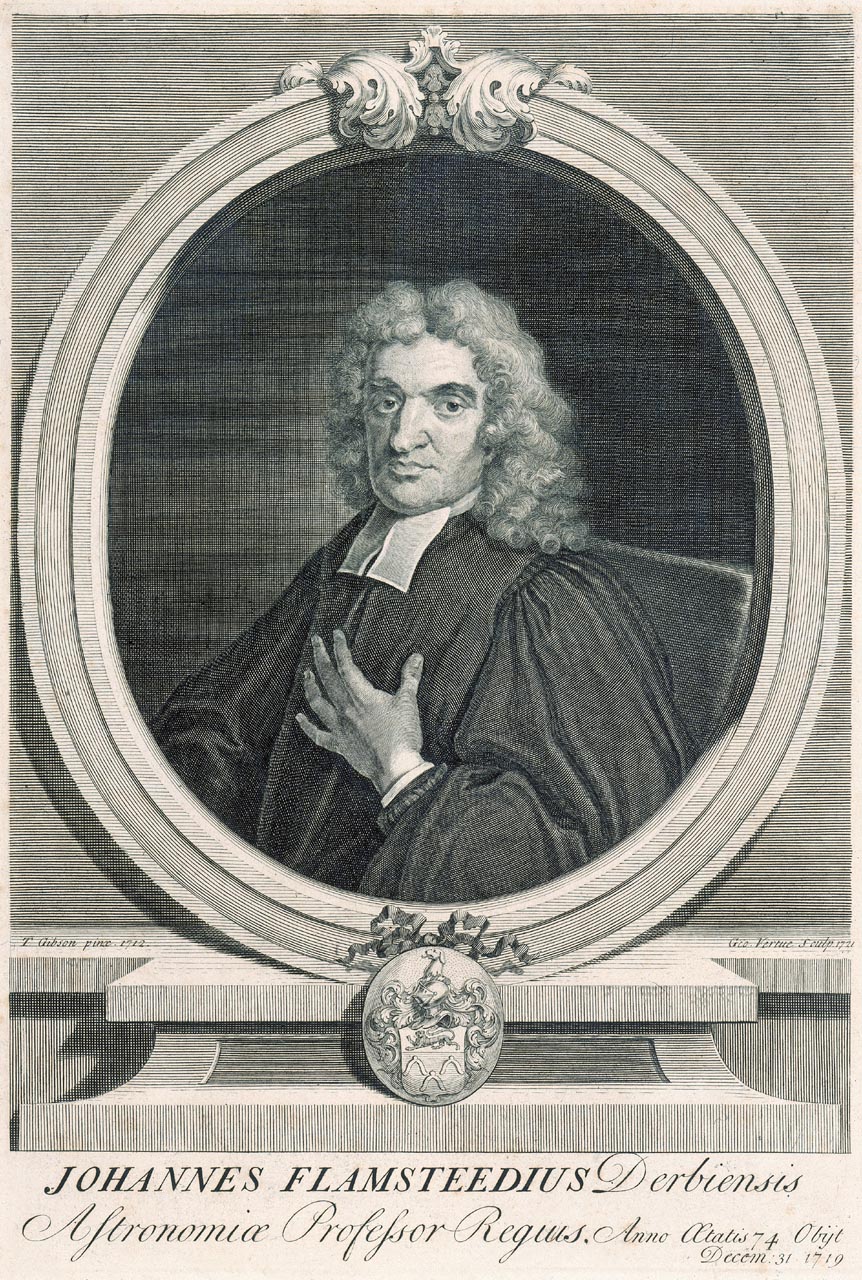

What interests me particularly about these portraits, and others of the period like Humphry Davy or William Whewell, is that they depict relatively young men, in a period when youth, imagination, intellect and genius were unabashedly romanticised and celebrated. Although there are plenty of exceptions to the rule, before this date portraits often appear more formal, and later the dominance of photography brings a distinctly unflattering stiffness or realism to our heroes. By and large, too, men of science tended not to have portraits done until they had reached rich or honoured old age, usually long after their best work was behind them. And how much do they affect our assumptions? Flamsteed, the first Astronomer Royal is usually thought of as dull, plodding, uptight and downright grumpy. There is certainly plenty of this in what his wrote in old age, and it is underlined by our best-known image of him, a frontispiece to a posthumous volume, but do we think a little more kindly of him when presented with his more youthful image?

These themes are particularly pertinent in a museum setting. People and the personal are very often dominant in our displays, either reflecting the kind of material that has been collected (relics, provenances) or assumptions about how audiences best respond to the themes we are treating. If you want people to care about the bunch of stuff (scientific instruments, documents, tools, trinkets, whatever) we are showing, the usual tactic is to provide a name, some biography and a portrait. If those portraits evoke sympathy and interest, all the better. Thus, while I have concluded that my ’19thC scientific hotties’ are not the answer to eschewing anniversaries as a hook for introducing my historic characters, I nevertheless found it helpful to think about personal reactions to these images, with their ability – part of their original intention – to inspire the viewer with a whole range of emotions.

[…] vocabulary, and nor is a focus on people’s looks. And thus an explanation is in order… [Read more] Share this:Like this:LikeBe the first to like this […]

Surely Faraday was discreet rather than discrete?

I wonder which 19th century mathematicians were good-looking?

Well-spotted, although if we take discrete as “apart or detached from others; separate; distinct”, then I think it might be possible to apply it to Faraday in his private life.

On mathematicians, I think we might include Whewell, linked above. Any other ideas out there?

Try Niels Abel

Love these reflections. I’ve been fascinated for a while about the trend of approaching historical figures through their physical attractiveness — their “bangability,” as some would have it. I think it’s generally harmless, and at least occasionally manages to introduce historical figures who might otherwise remain obscure to some. It’s always a little startling, though, when I get a comment on my blog (as is always the case when I trot out Robert Cornelius) that the guy is “actually pretty cute for a 19th century guy.” As if attractiveness were some sort of recent innovation.

But maybe that’s what works about this approach — shattering the idea that the past is such a different country that these folks were never young, were never vain and uncertain (or brash and overconfident as the case may be), just like lots of us were. Or are. I’m a writer and prefer words to pictures, so I like to connect with historical folk by reading biography. More visual people might connect better with portraits. But yeah, there’s no doubt that it’s also playing on our shallow tendency to feel more sympathy for the young and good looking. I try to take it all with a hefty grain of salt.

Many thanks for your thoughtful comments – I agree that its an issue that raises all sorts of interesting problems and questions. The trouble with portraits is that, until very recent history at least, we usually only have one or a handful of images to judge, and they are – by their nature – very deliberate, posed, and mediated. It is as if we only had someone’s biography or autobiography to work from and no published work, correspondence or notebooks.

Rebekah, if you haven’t already checked out this blog:

http://fuckyeahhistorycrushes.tumblr.com

(apologies for the NSFW title), you MUST. I myself submitted uber-hottie public hygienist Max von Pettenkofer on page 22.