Earlier this month I published a post at the H Word on ‘Halley’s Eclipse’ of 1715. It has been associated with Edmond Halley because, using the best theory and data then available, he made impressively accurate predictions of its timing and path, publicised through a broadsheet map and the Royal Society. As I explain in the post, however, he was not the only one to do so: London was a competitive market for scientific publications and authority.

This post is an appendix, where I can show more of the eclipse maps published than I could on the Guardian’s website. I should add, too, that these were not the first predictions or maps of solar eclipses, and that there were earlier German, Dutch and French maps.

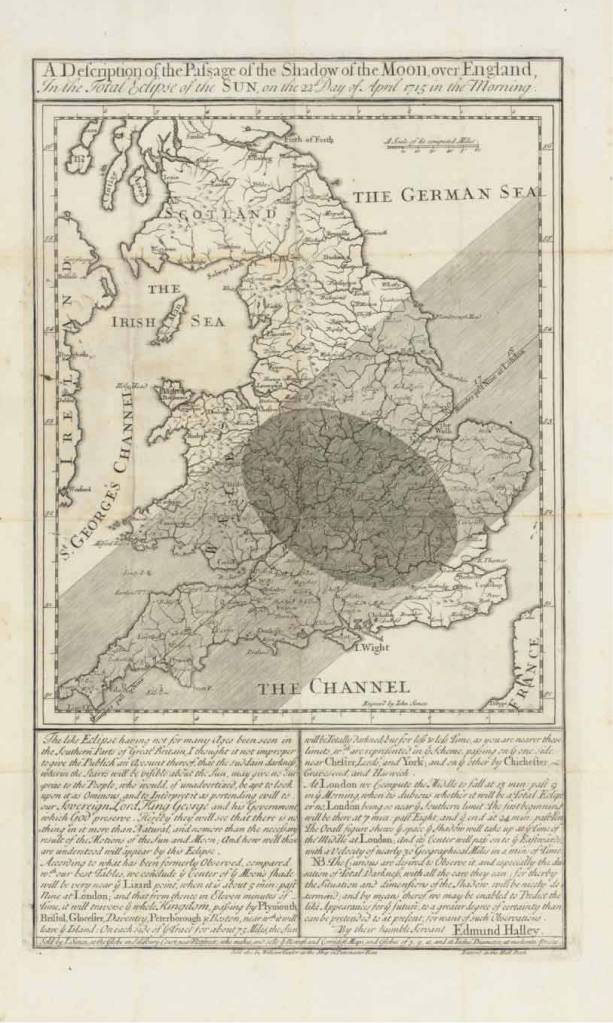

Here, however, is Halley’s first map, from Eclipse Maps, which was published in advance of the event, encouraging observation. It is titled “A Description of the Passage of the Shadow of the Moon over England, In the Total Eclipse of the Sun, on the 22d Day of April 1715 in the Morning”. I am not sure where the original is kept, but it may be the same as that reproduced in black and white in Jay Pasachoff’s article on Halley’s eclipse maps, which is from the Houghton Library. The full text, which is not high enough resolution to read here, has been transcribed by Pasachoff.

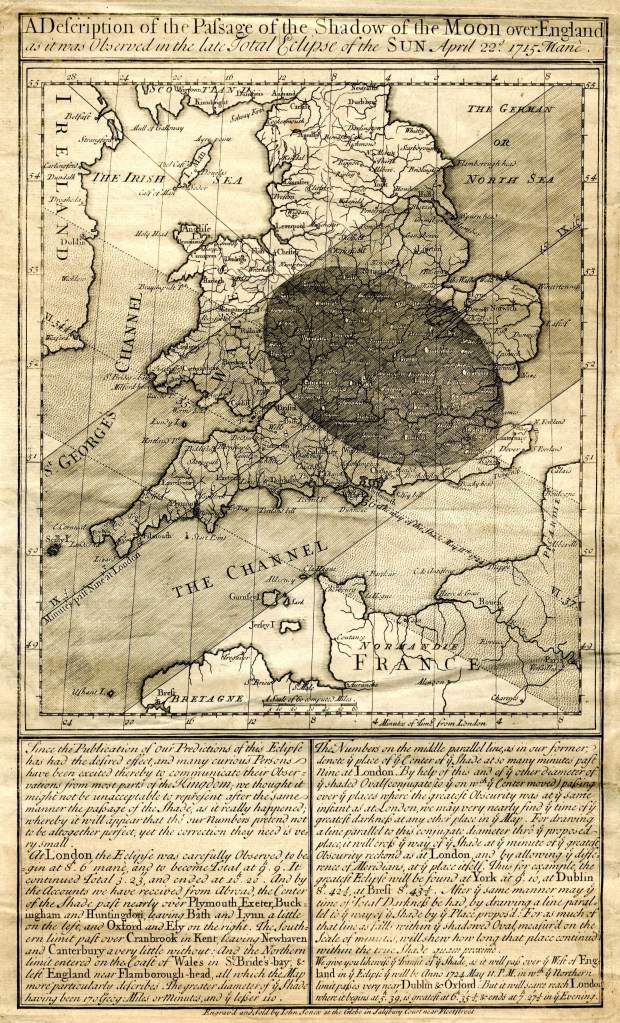

Halley seems to have produced more than one edition of the map before 22 April 1715 (O.S. – the anniversary was celebrated on 3 May N.S.), and also one after the event, showing the path as corrected by observations. This copy of his “A Description of the Passage of the Shadow of the Moon over England as it was Observed in the late Total Eclipse of the Sun April 22d, 1715 Manè” is from the Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, where you can see some superbly high-resolution images.

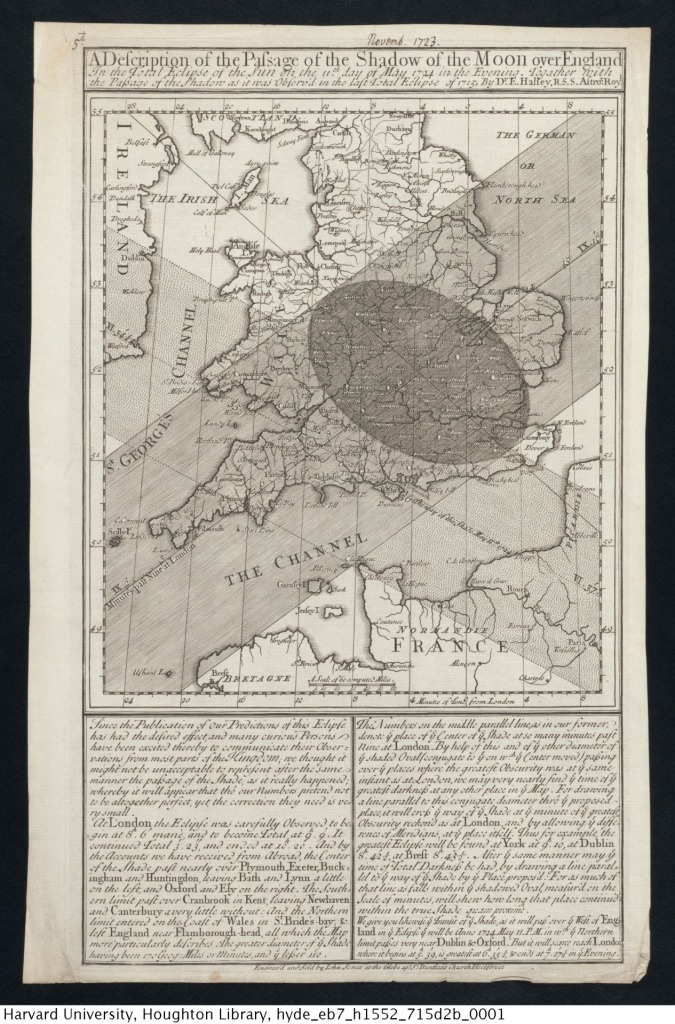

Halley came back to his winning formula when another eclipse rolled along. His map, published in 1723 (annotated November 17123 here), showed both the recomputed path of the 1715 eclipse and the predicted path of 11 May 1724. This image is from the Houghton Library’s Tumblr, where it is available in higher resolution. The text declares that the first map “has had the desired effect” in encouraging observation and uses this one to demonstrate that his predictions had been pretty good in 1715 and were worth acting on again.

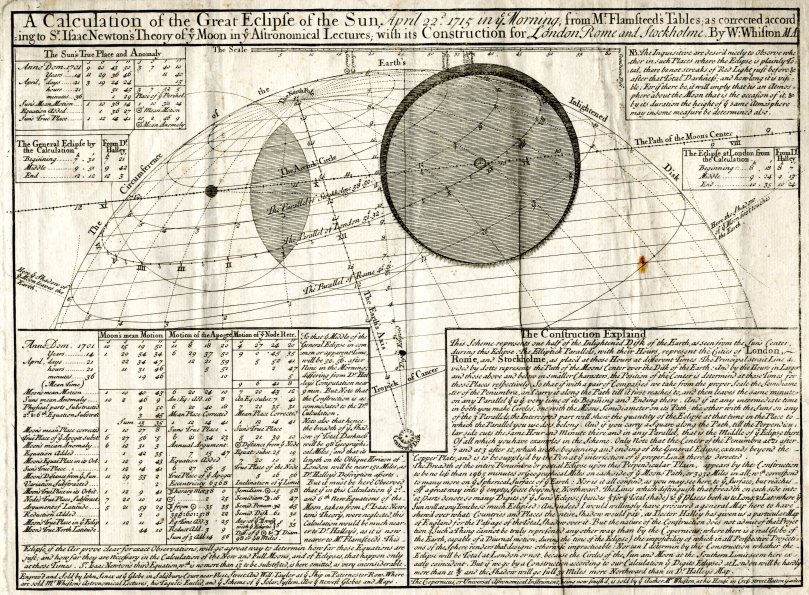

However, as my post discussed, William Whiston was also in the business of predicting eclipses and selling scientific paraphernalia. Like Halley, he was making predictions based on John Flamsteed’s observations at the Royal Observatory and corrected with Isaac Newton’s theory, and encouraging observations. Whiston made comparison of his observations with Halley’s and his two eclipse-predicting broadsheets are again from the Cambridge Institute of Astronomy’s Library here and here.

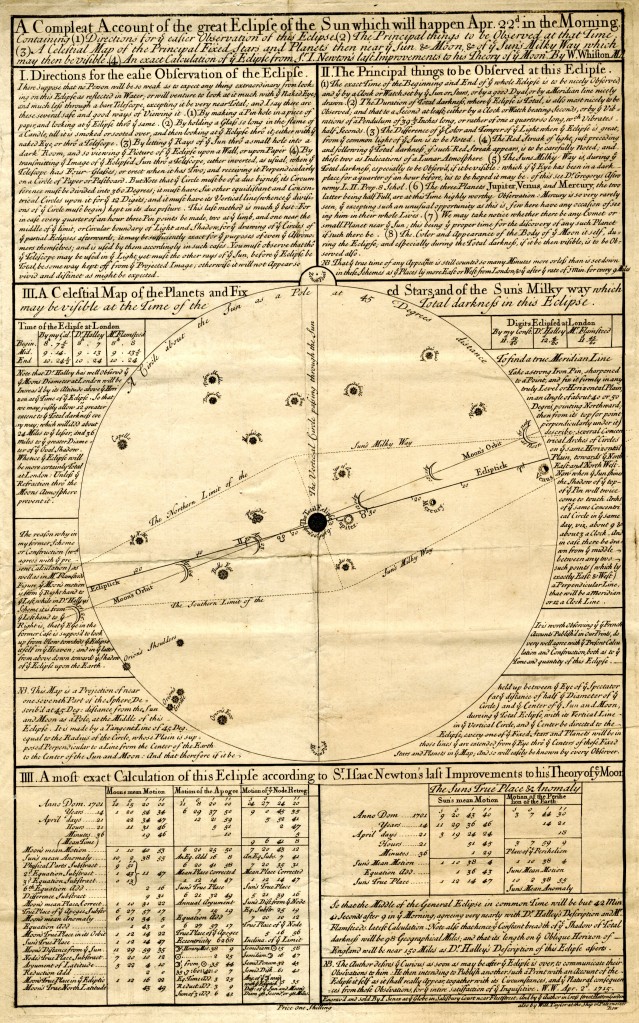

The one I think is the earlier from Whiston was dated 2 April 1715 and titled “A Compleat Account of the great Eclipse of the Sun which will happen Apr. 22 in the Morning”. It is much more text-heavy and technical in content, and the map is a celestial one, showing the positions of the heavenly bodies rather than the path of the shadow on Earth.

A second broadsheet by Whiston did show the Sun’s shadow on the Earth, but from a global point of view. The title too emphasised that this was not just an English matter: “A Calculation of the Great Eclipse of the Run, April 22d 1715 in ye Morning, from Mr Flamsteed’s Tables; as corrected according to Sr Isaac Newton’s Theory of ye Moon in ye Astronomical Lectures; with its Construction for London Rome and Stockholme”. It also advertised an instrument that could be bought from Whiston.

John Westfall and William Sheehan’s new book on observing eclipses, transits and occultations, indicates the Whiston and Halley’s estimates varied by about 25 miles, which perhaps puts the more triumphant claims of accuracy in perspective. I think (correct me below if I am wrong) that Halley’s prediction was the more accurate, but there was an element of luck involved. Above all, his map, showing geographical detail of England beneath the path of totality, was much more persuasive and appealing – this is the main reason that the 1715 eclipse became ‘Halley’s’.

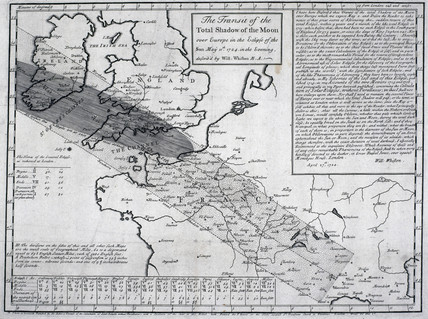

Whiston had learned the importance of the image by 1724. His “The Transit of the Total Shadow of the Moon” this time showed familiar coastal outlines, although again other parts of Europe were included: Paris would be a better observing site than London this time. This version is from the Science & Society Picture Library and belongs to the Royal Astronomical Society.

And so the maps continued: there are many to explore in the wonderful albums at Eclipse Maps. It was a flourishing business come eclipses in the 1730s and beyond, especially that of 1764, as many publishers jumped on the opportunity that Halley and Whiston had spotted in 1715. So too, of course, had the person that links all the images shown here: the engraver and cartographer John Senex, who deserves a much fuller biography on Wikipedia than this!

The craftsmanship that went into those maps is amazing to me; it is difficult to imagine a modern scientist in a harried lab spending long hours putting calligraphy pen to paper and drawing such geometric curves with their own two hands. A beautiful product.

I would like to know more about the process by which these broadsheets were produced – I’m sure they made good use of the skills of professional cartographers, draftsmen and engravers. It seems clear, though, that Halley had a good eye for how maps could be used to carry different kinds of information.

One wonders about the print run for this kind of broadsheets, who read them, how they were distributed &c. (This is not my century, I mostly do 19th and 20th century astronomy, so the question is probably banal.) In Sweden, the closest analogy I can think of are the almanacs of the early 18th century containing eclipse predictions; they were of course bestsellers but their graphical layout – I’ve looked a bit at early 18th c. almanacks by Birger Vassenius – are a lot less impressive than these magnificent broadsheets. Imagine buying them at a bookseller’s shop some months before the eclipse!

It is difficult to find out print run and distribution, although the prices are know (6d for Halley’s first map). There is some detail about the advertising in Alice N Walters’ 1999 article on eclipse broadsides (the whole issue of History of Science it appeared in is available as a PDF here: http://www.shpltd.co.uk/hs.pdf), also Pasachoff’s article linked above. I suspect claims for the effectiveness in terms of promoting useful observations were probably rather over-stated, but evidence of second editions and so on suggest they were popular.

[…] teleskopos: Eighteenth-century eclipse maps by Halley and Whiston […]

[…] The Empire Trees Climate project is an excellent example of the connection between environmental history and science and the value of interdisciplinary cooperation. This month the project provides its third research profile of Kimberly Monk, a maritime archaeologist, who is a part of the project. Matthew Holmes, a PhD Student in the History and Philosophy of Science, reviews The Future of Scientific Practice. Holmes provides a great deal of interesting posts on environmental history and the history of science on his blog, Thinking Like a Mountain: The Weird & Wonderful in the History of Science & the Environment. On the Royal Society’s blog, The Repository, Anne Marie Roos discusses the importance of personal diaries and papers of past scientists for understanding the history of science, in “The Paper Chase.” And on Teleskopos, Rebekah Higgett looks at the “Eighteenth-Century Eclipse Maps of Halley and Whiston.” […]