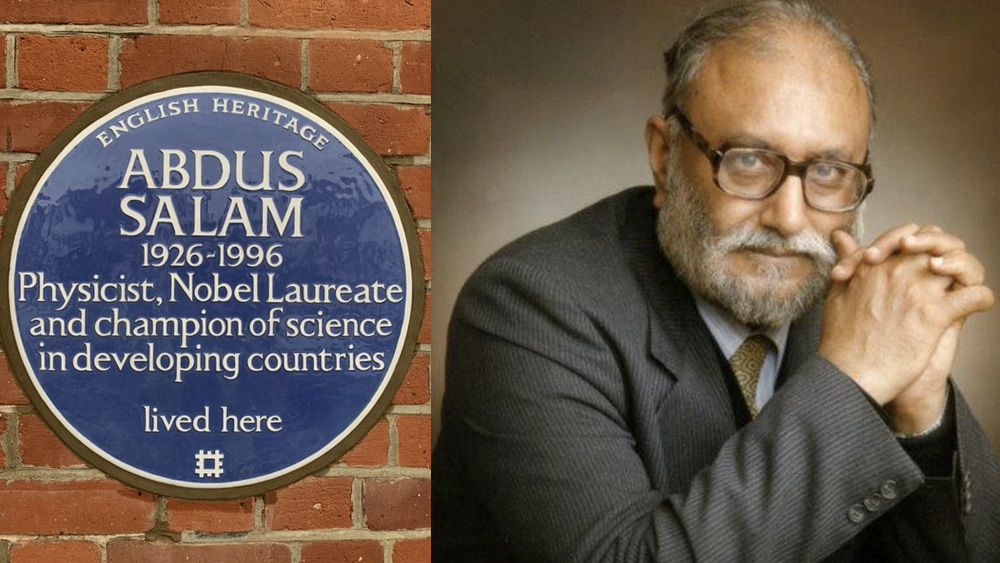

Today English Heritage unveils a new blue plaque to the theoretical physicist and Nobel Laureate Abdus Salam (1926-1996), with an appeal for more nominations for scientists to increase their representation in the London scheme. As a historian of science sitting on their Blue Plaque panel, I am delighted to support this call.

Scientists and natural philosophers account for around 15% of the more than 950 blue plaques in London. Some of these will be found categorised under medicine or engineering but the scheme lists just 66 plaques online under the category of science, in contrast to 102 as fine arts, 171 politics and 213 literature. These numbers are a product of the scheme’s earlier history, under the Society of Arts, London County Council and Greater London Council, as well as of broader cultural assumptions about who and what should receive such marks of public esteem.

The contributors to science honoured by blue plaques include key figures of the 17th-century Royal Society, Isaac Newton and Christopher Wren, as well as household names such as Charles Darwin and Alan Turing. But our understanding of science suffers if it encourages an assumption that its progress has been due only to a few geniuses, usually white and male, and often seen as working in isolation from society.

Happily, this scheme also recognises a whole range of other contributors and contributions. One plaque marks the Holborn site of the shop and workshop of the watchmaker Thomas Earnshaw, another the home of the Scottish plant collector and ‘tea thief’ Robert Fortune, and in Hackney we find a plaque to the zoologist Philip Gosse. The new plaque to Salam reminds us that not all eminent contributors to science in London were white or born in the west.

There are also, especially after recent calls for nominations, several plaques marking women scientists. These include the increasingly celebrated figures of Ada Lovelace and Rosalind Franklin but also a number whose plaques should help them to be more widely recognised, such as the botanists Agnes Arber and Helen Gwyenne-Vaughan and the electrical engineer and physicist Hertha Ayrton.

One of the distinctive features of the scheme is that a building associated with a nominated figure should still survive. While this limits who can be put forward, it has the benefit of encouraging us to think about these individuals in context – not just as those who contributed ideas and information to their scientific field, but as people who lived and worked, loved, laughed and prayed, across London’s boroughs. Science is a human endeavour that is not, and never has been, isolated from place.

The biases of building survival, as well as the wealth and connections that are often prerequisites for success, mean that many blue plaques are found on substantial buildings in places like Westminster, Kensington and Chelsea. But we find that other locations and a wide variety of stories are revealed by these combined markers of place and people.

Abdus Salam’s plaque is on a red-brick Edwardian house in Putney, his London base from 1957 until his death in 1996. While the wording of the plaque tells of his international fame and role in championing science in developing countries, the location is residential, a home where he studied and wrote, and listened to music and Quranic verses on his record player.

The very first plaque to a scientific figure, unveiled by the Society of Arts in 1876, is in Marylebone. It celebrates Michael Faraday (1791-1867), known for his discoveries in electromagnetism at the Royal Institution. However, the plaque records that he was ‘Apprentice here’, for the building is where he worked not as a chemist but as a bookbinder. His apprenticeship moved him from Newington Butts in Surrey to a building from which he could attend scientific lectures.

In Hackney, though sadly not currently visible from the street, there is a plaque to Joseph Priestley (1733-1804). A chemist, best known for his discovery of gases, including Oxygen, Priestley was also a teacher and preacher. His plaque, calling him ‘Scientist, Philosopher and Theologian’, tells us that this was the site of the Gravel Pit Meeting, a nonconformist religious congregation to which Priestley was minster.

While Priestley’s is one of the wordier plaques, it is another man of science who has one of the most evocative. This is Luke Howard (1722-1864), described as ‘Namer of Clouds’. He was the amateur meteorologist who proposed the classification and Latin names for clouds. He was also a manufacturing chemist of means, whose plaque is at 7 Bruce Grove in Tottenham. Now owned by developers it is currently vacant and at risk, with campaigners hoping to save it from further deterioration. As the site of Tottenham’s only blue plaque, and a Grade II listed building, it would be a tragedy to lose Howard’s former home.

English Heritage, and the Blue Plaque panel, rely on the public to make proposals for plaques such as these. They particularly welcome those that help reveal the significant stories that link scientists and London’s buildings.

![Prospectus intra Cameram Stellatam [View inside the Star Room] (Photo: National Maritime Museum)](https://teleskopos.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/octagon-room.jpg?w=645)